Tape recording was introduced 70 years ago today

It was 2 am on a spring night in 1944 — May 14, to be exact. And thanks to the good fortune of suffering from insomnia, a curious observation by John T. “Jack” Mullin led to the introduction of tape recording and, by extension, the entire home media business.

Mullin, a slight and surprisingly humble man, considering his future status in the recording business, graduated from the University of Santa Clara with a B.S. in electrical engineering in 1937, then worked for Pacific Telephone and Telegraph in San Francisco until the war started. By 1944, he had attained the rank of major in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and was attached to the RAF’s radar research labs in Farnborough, England.

While working late that spring night, Mullin was happy to find something pleasing playing on the radio — the Berlin Philharmonic playing Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony on Radio Berlin. But Mullin was mystified: The performance’s fidelity was far too fine to be a 16-inch wax disc recording, the prevailing radio recording technology at the time. And since there were no breaks every 15 minutes to change discs, Mullin figured it had to be a live broadcast. But it couldn’t be — if it was 2 am in London, it was 3 am in Berlin.

Mullin was right — the orchestra wasn’t up late, and it was a recording. Just not the usual kind, which is why Mullin was confused.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6484617/Image%201.jpg)

Up until the war, the west recorded using magnetic wire. Magnetic wire recording had been invented by the Danish engineer Valdemar Poulsen in 1898, then perfected, patented and commercialized by Marvin Camras in the 1930s. It was used by the armed forces during World War II and considered secret.

As a result, magnetic tape recording had been discussed on and off in radio circles for years, but no one had managed the feat — at least as far as anyone west of the Rhine was concerned.

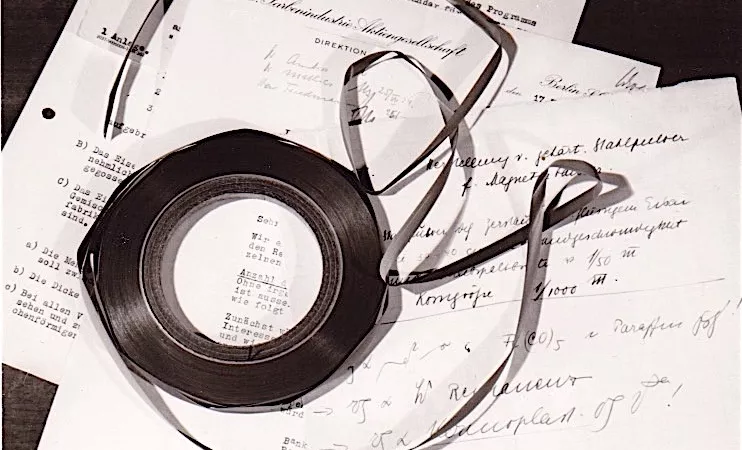

In 1934, Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft (AEG), the German division of General Electric, began manufacturing a tape recorder called the Magnetophon, which used plastic tape coated with magnetic particles and was manufactured by BASF. What individual German engineers managed this feat, we may never know. But over the next few years, AEG engineers expanded the Magnetophon’s fidelity from low-fi using DC bias to hi-fi using AC bias. By 1941, several of these hi-fi Magnetophons were placed in radio stations all over Germany.

With the possible exception of GE, no one had any knowledge of the technology.

Magnetophon discovery

After the war, Mullin was assigned to the Technical Liaison Division of the Signal Corp in Paris. “Our task, amongst other things, was to discover what the Germans had been working on in communications stuff — radio, radar, wireless, telegraph, teletype,” explained Mullin.

Mullin ended up in Frankfurt on one such expedition. There he encountered a British officer, who told him a rumor about a new type of recorder at a Radio Frankfurt station in Bad Nauheim. Mullin didn’t exactly believe the report — he had encountered dozens of low-fi DC bias recorders all over Germany. He pondered his decision of pursuing the rumor, literally, at a fork in the road. To his right lay Paris, to the left, Radio Frankfurt.

Fortuitously for the future of the home media business, Mullin turned left.

He found four hi-fi Magnetophons and some 50 reels of red oxide BASF tape. He tinkered with them a bit back in Paris and made a report to the Army. “We now had a number of these lying around. I packed up two of them and sent them home (to San Francisco). Souvenirs of war. (You could take) almost anything you could find that was not of great value. (And) anything Germany had done was public domain — it was not patentable.” He also sent himself the 50 reels of the red-oxide coated tape.

When Mullin returned home, he started tinkering to improve the Magnetophons. On May 16, 1946, exactly 70 years ago today, Mullin stunned attendees at the annual Institute of Radio Engineers (IRE) conference in San Francisco by switching between a live jazz combo and a recording, literally asking the question “Is it live or…?” None of the golden ears in the audience could tell. It was the world’s first public demonstration of audio tape recording.

Bing Crosby on the road to video

Bing Crosby hated doing live radio. And he hated recording his shows on wax records because the fidelity sounded terrible to the noted aural perfectionist performer. When Crosby’s engineers heard about Mullin and his Magnetophons, they quickly hired him and his machine. In August 1947, Crosby became the first performer to record a radio program on tape; the show was broadcast on October 1.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6484613/Image%203.jpg)

Crosby wasn’t the only one interested in Mullin’s Magnetophons. Up in Redwood City, Calif., a small company called Ampex was looking for something to replace the radar gear they’d been producing for the government. Ampex hooked up with Mullin and, in April 1948, perfected and started selling the first commercially available audio tape recorder, the Ampex Model 200.

Crosby, Mullin, Ampex and electronics titan RCA all sort of formulated the same follow-up thought at around the same time: If you could record audio on tape, why not video?

Crosby and Mullin teamed up. Ampex formed a team that included a high school student named Ray Dolby. And David Sarnoff gave his engineers their marching orders. A highly-public race began to see who could invent the video tape recorder.

But Ampex had a leg up on its more well-heeled competition. It had a deal with a Chicago research consortium called Armour Research Institute, now the Illinois Institute of Technology. Working for Armour was none other than wire recording maven Marvin Camras, who solved the most vexing problem facing all the video tape inventor wannabees: Tape speed.

Audio recording is accomplished by pulling tape past a stationary recording head. Video, however, is a far fatter signal, which meant tape had to be pulled past the recording heads at ridiculous speeds. A two-foot wide reel of tape could hold, tops, 15 minutes of video — not exactly practical.

So instead of spinning the tape, Camras, who got the idea from watching vacuum cleaner brushes, figured he’d spin the recording heads instead. Once Ampex got ahold of this key, its engineers shot past Crosby/Mullin and RCA.

Even with the spinning head secret, it took five years for Ampex’s sometimes part-time six-member team to get things right. On April 14, 1956 — 60 years ago last month — Ampex introduced the desk-sized Mark IV, the first commercial video tape recorder, to a stunned group of TV execs and engineers at the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) confab in Chicago. To say that this machine changed the world is an obvious understatement.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6484615/Image%204.jpg)

It would take almost another 10 years before Philips reduced audio tape to a cassette and ignited the home audio recording craze, and another nearly 10 years before Sony introduced the Betamax and won a Supreme Court case to allow us to legally record TV shows at home and create the home video business.

But it was the introduction of Jack Mullin’s rebuilt Magnetophons that were the first shots fired in the home media revolution, 70 years ago today.

Technology historian Stewart Wolpin has been reviewing consumer electronics for more than 30 years and writes about consumer technology for eBay. Reach him @stewartwolpin.

From tape to digital: The future of music

FONTE: http://www.recode.net/2016/5/16/11672678/tape-recording-70th-anniversary-jack-mullin

Julian Ludwig é diretor do Pro Áudio Clube, produtora de áudio Jacarandá, Loc On Demand e Jacarandá Licensing. Trabalhou para empresas como: Guaraná Antartica, TV Gazeta, NET, Chivas Regal, FNAC, Prefeitura de São Paulo, Mukeca Filmes, Agência LEW’LARA TBWA, Agencia MPM, Agência Content House entre outras. Fez trilhas para programas de TV como: Internet-se (Rede TV), Você Bonita (TV Gazeta), Mix Mulher (TV Gazeta), Os Impedidos (TV Gazeta), Estação Pet (TV Gazeta), CQC (TV Band) Vinheta Oficial TV Gazeta, entre outras. Também atuou em vários longas e curtas metragens, incluindo mixagem em 5.1 e serviços de pós-produção.